Is Sugar the Silent Killer in Your Senior Diet? How to Find Out if It’s Sneaking Onto Your Plate

A senior may start their day with a cup of flavored yogurt, a bowl of whole-grain granola, and a glass of orange juice, believing they have made a healthy choice. By 9 AM, however, they may have consumed over 30 grams of added sugar—more than the American Heart Association’s entire daily limit for a senior woman.

This is the “silent killer” in senior diets: the sugar that is consumed unknowingly. The core of the problem lies in a physiological reality: as the human body ages, it becomes less efficient at processing sugar.

This silent, chronic overconsumption of sugar in senior diets is not merely a matter of weight gain; it is a primary driver of the most feared conditions in aging, including Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and cognitive decline.

The Amplified Risk: Why Sugar Is a Top Health Threat for Seniors

The health risks of excess sugar consumption are amplified in older adults. This is not simply an additive risk, but a multiplicative one.

Aging itself is an independent risk factor for chronic disease, characterized by biological hallmarks like chronic, low-grade inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction. High-sugar diets have been shown in clinical studies to induce these exact same hallmarks.

This convergence creates a “double jeopardy” scenario. Research from 2022 indicates that the inflammation that naturally progresses with aging may “further predispose older individuals to dietary insults by fat and sugar”. In effect, the body’s natural aging process is a small, smoldering fire of inflammation.

Risk 1: The Direct Link to Type 2 Diabetes Mortality

For seniors, the link between diet and diabetes is a matter of life and death. The 2021 Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) study provided a stark statistic:

among adults aged 65 and older, specific dietary risks—including high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and low intake of whole grains—accounted for 23.61% of all Type 2 Diabetes-related deaths.

This figure connects specific dietary choices, like sugar intake, directly to mortality, moving it from a “lifestyle” issue to a critical, non-abstract threat. The prevalence of diabetes in the aging population is a central challenge in gerontology.

This is why the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2025 Standards of Care place such a heavy emphasis on nutritional therapy.

These standards recommend dietary patterns proven to manage metabolic health, such as the Mediterranean diet , and specify a high-fiber intake of 30 to 50 grams daily to help manage glycemic control.

Risk 2: The Cardiovascular Crisis and the “Liquid Sugar” Threat

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in the United States. The burden of this disease falls disproportionately on older adults.

The 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics update from the American Heart Association (AHA) illustrates this clearly: in 2020, 55.6% of all percutaneous coronary interventions (procedures such as implanting stents) were performed on individuals aged 65 or older.

High sugar intake is a direct contributor, known to raise blood pressure, fuel inflammation, and increase triglycerides, all of which strain the heart. However, recent research provides a crucial level of specificity.

A groundbreaking 2024 study published in Frontiers in Public Health analyzed different types of sugar consumption and found a divergent relationship. The study found that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs)—such as sodas, fruit juices, and sweetened teas—carry a notably higher risk for heart failure and stroke.

This finding points to a “liquid sugar” smoking gun. The average 12-ounce can of soda contains nearly 10 teaspoons of sugar, the maximum daily limit recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans for a 2,000-calorie diet.

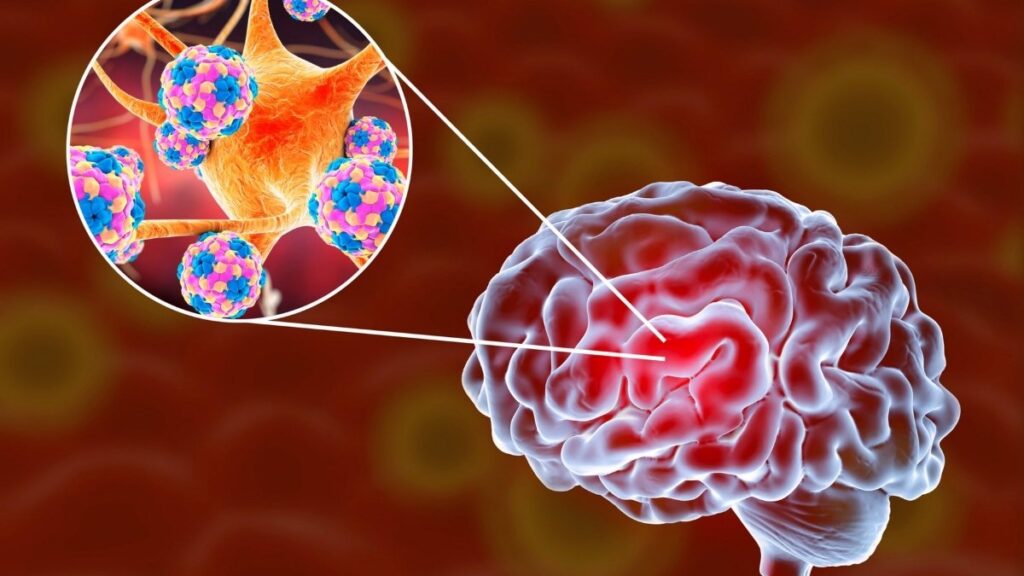

Risk 3: The Terrifying Link to Cognitive Decline (“Type 3 Diabetes”)

Perhaps the most frightening risk for seniors is the link between sugar and cognitive decline. The evidence for this is mounting and specific.

A 2024 longitudinal study published in Nutrients delivered a stunning statistic: community-dwelling older adults in the highest quintile of sugar intake had double the risk (a 2.10 Hazard Ratio) of developing dementia compared to those in the lowest quintile.

The same study drilled down on the type of sugar, finding that fructose—the primary sugar in high-fructose corn syrup and common in processed foods—had the strongest association, linked to a 2.8-times higher risk of dementia.

This points the finger directly at the hidden sugar in foods and drinks, not just table sugar.

This strong connection has led some researchers to propose the term “Type 3 Diabetes” to describe Alzheimer’s disease.

This is not an officially recognized medical diagnosis. Major health organizations, including the American Diabetes Association, do not classify Alzheimer’s as a type of diabetes.

There are two primary theories for this link:

Brain Cell Starvation: In this model, brain cells become resistant to insulin, just as muscle cells do in Type 2 diabetes.

Because insulin is required to help glucose enter brain cells, the neurons become “starved of glucose” , impairing their function and leading to the progressive memory loss characteristic of Alzheimer’s.

Amyloid Plaque Buildup: As explained by Nebraska Medicine neurologist Dr. Daniel Murman, the enzyme that breaks down insulin in the brain is also responsible for breaking down amyloid proteins (the main component of Alzheimer’s plaques).

In a state of high insulin (hyperinsulinemia), this enzyme is so busy breaking down insulin that it “neglects” the amyloid proteins, allowing them to build up and form toxic plaques.

While Dr. Murman cautions that it is “not accurate to say that all cases of Alzheimer’s disease are caused by diabetic mechanisms” , the underlying relationship is undeniable.

People with Type 2 diabetes have a significantly higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. This makes controlling sugar a primary strategy for protecting not just the heart, but also the brain.

As neuroendocrinologist Dr. Robert Lustig stated in a 2025 AARP interview, “Sugar is a primary driver of the aging reaction. The more sugar you eat, the quicker aging will occur”.

Where Sugar Hides: A “Sugar Sleuth’s” Guide to “Healthy” Frauds

One of the greatest challenges for seniors is that the primary source of excess sugar is not the dessert table; it is the “healthy” foods consumed every day.

The issue is added sugars—sugars added during processing—not the naturally-occurring sugars in an apple or a glass of plain milk.

These are added to enhance flavor (especially in “low-fat” products, which often trade fat for sugar) and to act as a preservative, extending shelf life.

The disconnect is stark. The average American adult consumes 15 to 19 teaspoons of added sugar daily. For optimal senior health, the 2025 American Heart Association guidelines recommend a much stricter limit:

- For senior women: No more than 6 teaspoons (25 grams) per day.

- For senior men: No more than 9 teaspoons (36 grams) per day.

The following “healthy” food categories are the primary culprits responsible for this massive overconsumption.

The Breakfast Betrayal: Yogurts and Cereals

The “health halo” surrounding breakfast foods is the most pervasive. A 2024 analysis from Eat This, Not That! noted that while a Dunkin’ Jelly Donut has 13 grams of sugar, some popular “healthy” yogurts contain significantly more.

Yogurt: The fruit-on-the-bottom and flavored varieties are essentially desserts. Examples of high-sugar “frauds” include Dannon Fruit on the Bottom Cherry (15 grams of sugar) and So Delicious Coconut milk Yogurt (16 grams of sugar).

The healthy “fix” is to choose plain, unsweetened yogurts, which contain 0 grams of added sugar. Top picks from registered dietitians include Siggi’s Plain Skyr and Fage Total 5% Plain Greek Yogurt.

Cereals & Granola: Many products marketed as “whole grain” or “high fiber” are loaded with sugar. For example, some Nature Valley granolas contain 9 grams of added sugar per serving.

The #1 heart-healthy “fix,” according to the British Heart Foundation, is plain porridge (oatmeal), which has no added sugar and contains cholesterol-lowering beta-glucans. Other good options include cereals with less than 8 grams of sugar per serving, such as certain Kashi GoLean varieties.

The Savory Deception: Sauces, Condiments, and Breads

Sugar is also hidden in savory foods where it is least expected. Jarred pasta sauces, ketchups, barbecue sauces, and even salad dressings are notoriously high in sugar.

Sauces: Many popular jarred pasta sauces contain 8 to 12 grams of sugar per half-cup serving. The “fix” is to find “no added sugar” brands. Brands like Rao’s and Victoria are often recommended because they use whole tomatoes instead of sugary tomato purée and contain 0 grams of added sugar.

Breads: Many commercial whole-wheat breads use sugar to enhance flavor and texture. A healthy “fix” is to check the label for 0 grams or less than 1 gram of added sugar per slice.

This scannable table provides a clear, actionable guide for caregivers and seniors at the grocery store.

The Savory Deception!

Watch for Hidden Sugar!

- Sauces: Many pasta sauces have 8-12g of sugar. Look for “no added sugar” brands like Rao’s or Victoria.

- Breads: Many whole-wheat breads add sugar. Check the label for 0g or <1g of added sugar per slice.

🚫 The “Fraud”

Dannon Fruit on the Bottom

15g Sugar✅ The “Fix”

Fage 5% Plain Greek Yogurt

5g Sugar🚫 The “Fraud”

Nature Valley Granola

9g Sugar✅ The “Fix”

Plain Porridge/Oatmeal

<1g Sugar🚫 The “Fraud”

Standard Jarred Marinara

8-12g Sugar✅ The “Fix”

Rao’s Homemade Marinara

4g Sugar🚫 The “Fraud”

12oz Can of Soda

~30-40g Sugar✅ The “Fix”

Water / Unsweetened Tea

0g SugarYour 2025 Action Plan: A 4-Step Guide to Cutting Sugar

This four-step plan provides a simple, sequential, and empowering approach to reducing hidden sugar in foods.

Step 1: Know Your Daily Limit (The Target)

A clear goal is the first step to success. While the general Dietary Guidelines for Americans set the upper limit for added sugar at 10 percent of daily calories, which is about 50 grams, the AHA 2025 guidelines are stricter and better for senior health.

These guidelines recommend that women over 65 should have no more than 6 teaspoons or 25 grams of added sugar per day.

For men over 65, the limit is slightly higher at no more than 9 teaspoons or 36 grams per day. To help visualize this, a single 12-ounce can of regular soda alone contains about 10 teaspoons of sugar.

Step 2: Become a Master Label-Reader (The Skill)

The most critical skill for identifying hidden sugar is learning to read labels. The best trick is to ignore the claims on the front of the box and turn it over to the Nutrition Facts label.

On that label, the most important number to find is the “Added Sugars” line, which is listed right below “Total Sugars.” You can also use the percent Daily Value, or %DV, to quickly check a product.

If the %DV for added sugar is 5 percent or less per serving, it is considered low. If it is 20 percent or more, it is considered high.

Learn Sugar’s Aliases: If “Added Sugars” are high, the ingredient list will reveal why. Sugar hides under many names. If any of the following are in the first three ingredients, the food is high in sugar:

- High-fructose corn syrup

- Sucrose

- Dextrose

- Maltose

- Cane sugar (or evaporated cane juice)

- Malt syrup

- Agave nectar

- Invert sugar

- Molasses

Step 3: Implement the “Whole-Food Fix” (The Strategy)

The simplest way to win the game is to eat foods that do not require a label. As one AARP member commented, “The best foods for you don’t have labels”. This means shifting the diet’s foundation to whole, unprocessed foods.

Nutritionist Kalousek Ebrahimi’s advice for 2025 is to “Focus on whole fruits, vegetables, lean proteins and healthy fats”.

This strategy automatically eliminates nearly all added sugar.

- Swap sugary sauces for herbs, spices, lemon, or vinegar.

- Swap sugary cereal for plain oatmeal topped with real berries. The fiber in the whole fruit slows the body’s absorption of its natural sugar.

- Swap sweetened yogurt for plain Greek yogurt, and add a few whole blueberries for flavor.

This strategy is proven to work. AARP featured the story of 67-year-old chef Bob Blumer, who “exercised like a fiend” but was diagnosed as prediabetic. He was shocked, as he thought he ate well.

He “cooked his way out of” prediabetes by eliminating processed foods and focusing entirely on whole-food recipes. This case study is a powerful testament that even active seniors can be at risk from hidden sugars, and that a whole-food approach is the definitive solution.

Step 4: Use 2025 Tech & Resources (The Tools)

This process can be aided by simple, senior-friendly technology and authoritative resources. The long list of available apps can be overwhelming; this curated list is categorized by specific user needs for 2025.

Category 1: For General Sugar & Nutrition Tracking

Fooducate: This app goes beyond simple calorie counting. It analyzes food logs and provides guidance and tips to “eat right,” making it ideal for those learning to change their habits.

MyFitnessPal: With one of the largest food databases, this app makes it easy to log packaged foods (often via barcode) and specifically track the “Added Sugar” nutrient total throughout the day.

Category 2: For Diabetes & Blood Sugar Management

mySugr: Frequently ranked as a “Top Diabetes App,” mySugr features a friendly, easy-to-use logbook for tracking blood glucose, carbs, and medications. Its key feature is the ability to generate daily, weekly, and monthly reports that can be shared directly with a doctor.

Glucose tracker – Diabetic diary: This app is praised for its simple, personalized tracking of blood glucose levels.

Category 3: For Caregivers & Families

Gluroo: This app is designed specifically for a support network. Its “GluCrew” function allows caregivers and family members to share real-time glucose data and log meals and doses from multiple devices, providing peace of mind and coordinated care.

Authoritative Resources: For continued, trustworthy reading, seniors and caregivers should turn to these sources:

AARP: The health section provides relatable, expert-vetted guides on senior nutrition.

American Heart Association (AHA): The definitive source for heart-healthy eating and sugar limits.

American Diabetes Association (ADA): The authority on nutritional therapy for managing blood sugar.

Conclusion

Reducing the amount of sugar in senior diets is not a practice of deprivation; it is a critical, evidence-based strategy for promoting health and longevity.

The threat of excess sugar for older adults is unique and amplified, with proven, direct links to the acceleration of Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decline.

The solution, however, is not complex. The problem is the hidden sugar, and the solution is awareness. By understanding the strict 2025 AHA limits (6-9 teaspoons), mastering the “Added Sugars” line on the nutrition label, and shifting focus to a whole-food diet, individuals can regain control of their metabolic health.

Making one smart swap at a time—such as plain yogurt for flavored, or water for soda—is not just a dietary change. It is a powerful, protective act for the heart and the brain.

An effective first step for any individual is to conduct a personal audit. For three days, without changing any habits, one should simply read the “Added Sugars” label on every food and drink consumed.

The results of this audit are often shocking and provide the necessary, tangible evidence to motivate a shift toward a healthier, more aware low sugar diet for seniors.