How to Build a Senior-Friendly Plate: The 7 Foods You Need and 5 to Avoid (Most Seniors Get This Wrong)

As we age, health concerns often focus on blood pressure or joint pain, but a hidden crisis is quietly impacting millions: senior malnutrition. Many older adults and caregivers are confused by conflicting diet advice , worried about decreased appetite , or seeing signs of frailty.

This is a documented trend, with malnutrition-related deaths rising and almost 7 million seniors facing food insecurity in 2022. This article provides a clear blueprint for building a senior-friendly plate.

It cuts through the confusion by focusing on nutrient density, the concept of getting more nutrients from fewer calories. We will detail the 7 essential foods you need for senior nutrition and the 5 you must limit, all backed by 2025 guidelines for building a healthy plate for seniors.

The Nutritional Reality of Aging: The “More-for-Less” Paradox

The foundation of health in the senior population is built upon a fundamental, and often misunderstood, nutritional concept: the “more-for-less” paradox. As individuals age, the body undergoes significant physiological shifts that alter its basic metabolic requirements.

Resolving this paradox—the need for more nutrients from fewer calories—is the single most important objective for maintaining health, resilience, and quality of life. The “Senior-Friendly Plate” is the strategic tool for achieving this goal, transforming abstract nutritional science into a practical, daily framework.

The Central Challenge: Fewer Calories, More Nutrients

The primary driver of the nutritional paradox is a change in both metabolism and body composition. Research from Tufts University and others highlights that, as individuals age, caloric needs typically decline.

This is due to a natural slowing of the body’s metabolic rate and a common shift in body composition: a gradual loss of lean muscle mass and a corresponding increase in adipose (fat) tissue, a state that requires fewer calories to maintain.

However, while the energy requirement (calories) decreases, the requirement for essential nutrients (vitamins, minerals, and specific macronutrients like protein) remains the same, and in some critical cases, increases.

This creates a nutritional chasm where there is significantly less room for “empty calories”—foods high in energy but low in nutritional value. For an older adult, every food choice must be a “nutrient-dense” one, selected for the high concentration of vitamins and minerals it provides per serving.

This mandate for high-quality, nutrient-rich foods forms the central challenge of senior nutrition.

Lessons from Longevity: Calorie Restriction and Blue Zones

This modern nutritional challenge is illuminated by decades of research into longevity, both in clinical and population settings. The only known nutritional intervention with the potential to “attenuate aging” and increase life span is calorie restriction (CR).

Clinical trials, such as the CALERIE study, have investigated the effects of reducing dietary intake below energy requirements while maintaining optimal nutrition. This research suggests that such a strategy can moderate the intrinsic processes of aging and reduce the risk for cardiometabolic diseases.

While controlled clinical trials on CR provide a biological basis for its benefits , real-world evidence from “Blue Zones”—regions known for exceptional longevity—demonstrates this principle in practice.

These populations, including those in Okinawa, Sardinia, and Ikaria, share common dietary patterns that are predominantly plant-based and high in whole grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables.

The new clinical consensus, supported by numerous studies and expert panels, suggests a higher target. Healthy older adults require a minimum of $1.0-1.2 / kg/day of protein to maintain muscle function.

For older adults who are exercising, or those managing acute or chronic illnesses, this recommendation increases to $1.2-1.5 g/kg/day.

Recent clinical trials provide direct evidence for these higher targets. A 2025 study examining elderly females (ages 60-75) with sarcopenia divided participants into two groups: one consuming the standard RDA (0.8 g/kg/day) and one consuming a moderately high intake ($1.2 g/kg/day) for 12 weeks.

The results were definitive: the $1.2 g/kg/day group showed significant improvements in muscle mass composition, as measured by MRI, as well as enhanced muscle function and strength. The standard $0.8 g/kg/day group did not see these benefits.

A separate 2025 study on middle-aged and older adults with Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM) reached a similar conclusion, stating that the $0.8 g/kg/day recommendation is “certainly not enough to ameliorate the muscle mass loss” and that an intake of $1.2-1.5 g/kg/day is “a more appropriate recommendation to combat upcoming sarcopenia”.

The Critical Importance of Protein Timing

While increasing total daily protein is essential, advanced research reveals a second, equally critical factor: protein distribution. It is not just the total amount of protein per day, but the amount per meal, that dictates its effect on muscle.

Older adults experience a phenomenon known as “anabolic resistance,” meaning their muscles are less responsive to the anabolic (muscle-building) signals of protein intake.

To overcome this resistance and trigger Muscle Protein Synthesis (MPS)—the biological process of building new muscle—a higher per-meal dose of protein is required compared to younger adults.

Research has identified a “protein threshold” of approximately 25 to 30 grams of high-quality protein per meal as the optimal amount to maximally stimulate MPS in older adults.

This finding exposes a critical flaw in the typical eating patterns of many seniors. The common dietary pattern involves a minimal protein breakfast (e.g., toast or cereal), a moderate protein lunch (e.g., a small sandwich), and a single, large bolus of protein at the evening meal.

This back-loaded distribution effectively misses the opportunity to trigger MPS at breakfast and lunch. The small 10-15 gram protein breakfast fails to meet the 25-30 gram threshold, and any protein consumed above the threshold in the evening meal is often oxidized for energy rather than used for muscle building.

Therefore, one of the most impactful, actionable strategies for combating sarcopenia is not simply to “eat more protein,” but to redistribute daily protein intake with the goal of achieving the 25-30 gram threshold at every meal, especially breakfast.

Research shows that consuming a higher protein breakfast is strongly associated with a higher total daily protein intake, making it a foundational strategy for rebuilding and maintaining muscle.

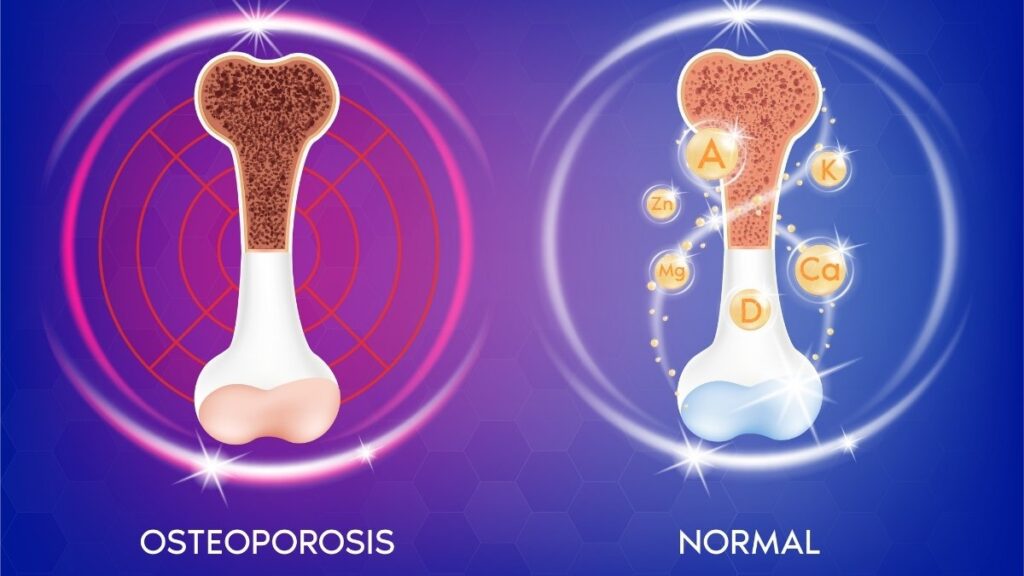

Defending Bone Integrity: Osteoporosis and the Calcium-D-B12 Triad

Alongside muscle loss, bone loss—or osteoporosis—represents a silent and staggering public health crisis.

In the United States, an estimated 10 million people aged 50 and older have osteoporosis, with an additional 43 million having low bone mass (osteopenia), which places them at high risk.

The prevalence increases dramatically with age. Worldwide, the disease affects an estimated one in three women and one in five men over the age of 50.

Nutritional intervention is a cornerstone of bone defense, centered on a synergistic triad of key nutrients.

The Synergistic Nutrients: Calcium & Vitamin D

Calcium is the primary mineral responsible for bone structure and strength. As individuals age, their need for calcium increases to offset bone loss. Vitamin D is equally critical, as it is essential for the body to absorb and utilize calcium.

The “Senior-Friendly Plate” must be structured to meet the specific, age-adjusted RDAs for both.

Calcium: Federal dietary guidelines recommend 1,000 mg per day for men aged 51-70. This increases to 1,200 mg per day for all women aged 51+ and all men aged 71+.

Vitamin D: Requirements also increase with age. Adults aged 51-70 need 600 IU (15 mcg) per day. This increases to 800 IU (20 mcg) per day for all adults aged 70+. Vitamin D can be obtained from fatty fish, fish liver oils, and, most commonly, from fortified foods like milk, milk products, and cereals.

The Overlooked Deficiency: Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is repeatedly identified as a “nutrient of concern” for older adults. While its RDA is 2.4 mcg per day, the issue for many seniors is not one of intake but of absorption.

This presents a critical, non-obvious nutritional challenge. Vitamin B12 found naturally in foods (like meat, fish, and poultry) is bound to proteins. To be absorbed, this B12 must first be cleaved from its protein by stomach acid.

However, as people age, stomach acid production often decreases—a condition known as atrophic gastritis, which is a key physiological change noted in older adults. Furthermore, the use of certain common medications can also reduce acid and B12 absorption.

This means that an older adult may have difficulty absorbing the B12 from “natural” food sources. The solution lies in fortified foods and supplements. The Vitamin B12 used to fortify foods like breakfast cereals or soy milk, as well as the B12 in supplements, is in a “crystalline” or unbound form.

This is a rare case where the “synthetic” version of a nutrient in a fortified food may be more effective and necessary than its “natural” counterpart, making fortified foods a key strategic element of the Senior-Friendly Plate.

Nutritional Intervention for Age-Related Chronic Disease

Beyond the musculoskeletal system, the “Senior-Friendly Plate” is a primary tool for the management and prevention of the most common chronic diseases of aging.

Hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease are endemic in the older population. Strategic, evidence-based nutritional choices are not merely complementary to medical treatment; they are a foundational component of it.

Hypertension: The Salt Substitute Solution and Its Critical Caveat

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a global epidemic, affecting an estimated 1.4 billion people worldwide. Its prevalence is deeply skewed toward older populations; in the United States, data from 2021-2023 shows that 71.6% of adults aged 60 and older have hypertension.

For decades, the primary advice has been sodium reduction. However, a major 2024 cluster-randomized trial, the DECIDE-Salt study, provided a powerful new intervention.

The study, conducted in adults aged 55 and older in residential care facilities, compared the effect of using regular salt (sodium chloride) with a potassium-enriched salt substitute.

The results were striking: the group using the salt substitute had a 40% lower incidence of new-onset hypertension compared to the regular salt group.

The mechanism was also clarified. The salt substitute did not just lower blood pressure; it prevented the significant increase in systolic blood pressure observed in the regular-salt group over the two-year period, all without increasing the risk of hypotension (low blood pressure).

These findings present a powerful, low-cost public health tool. However, this recommendation comes with a critical, expert-level warning that, if ignored, can be life-threatening. The advice cannot be given incompletely.

The mechanism of these salt substitutes involves replacing sodium chloride (NaCl) with potassium chloride (KCl). This strategy relies on the kidneys to safely process and excrete the increased load of potassium. A large and vulnerable portion of the senior population, however, has impaired potassium excretion.

This high-risk group includes two major categories:

- Individuals with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD).

- Individuals taking common blood pressure medications, specifically ACE inhibitors (e.g., Lisinopril, Vasotec) and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs) (e.g., Losartan, Cozaar).

Diabetes and Pre-Diabetes: Deconstructing the “Added Sugar” Label

The prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the senior population represents a public health emergency. According to the American Diabetes Association and CDC data, 29.2% (nearly one in three) of Americans aged 65 and older have diagnosed or undiagnosed diabetes.

Managing these conditions requires a focus on sugar intake, but this is complicated by a food industry that disguises sugar under a myriad of names. There are at least 61 different names for sugar listed on food labels.

These include not only sucrose (table sugar) and high-fructose corn syrup, but also dextrose, maltose, barley malt, rice syrup, agave nectar, and evaporated cane juice.

For years, consumers were hindered by nutrition labels that only listed “Total Sugars.” This single number was misleading, as it combined naturally occurring sugars (like lactose in milk or fructose in whole fruit) with sugars added during processing.

The most powerful tool for managing sugar intake is the updated FDA Nutrition Facts label, which now mandates a separate, indented line: “Includes [X]g Added Sugars”.

This single line is the key. It allows a consumer to compare two yogurts, for example. Both may have high “Total Sugars,” but one may have “Includes 0g Added Sugars” (from the natural milk sugar) while the other has “Includes 8g Added Sugars”.

The rule for reading the label is simple:

- 5% DV or less of added sugars is considered LOW.

- 20% DV or more of added sugars is considered HIGH.

The most practical, effective, and “senior-friendly” advice for managing diabetes risk is to ignore the “Total Sugars” line and shop exclusively by the “Added Sugars” line. Choosing foods and beverages with 5% DV or less of added sugars is a simple, data-driven strategy to control glucose intake.

Listeria Showdown: Avoid vs. Choose

High-Risk (AVOID) ❌

Unheated deli meats, cold cuts, or unheated hot dogs.

Cheeses made with raw (unpasteurized) milk. Also, Queso Fresco & Queso Blanco (even if pasteurized).

Premade store-bought salads (e.g., coleslaw, potato, chicken, or tuna salad).

Refrigerated pâté, meat spreads, or refrigerated smoked fish.

Raw or lightly cooked sprouts (e.g., alfalfa, bean).

Safer Choice (CHOOSE) ✅

Deli meats and hot dogs heated to 165°F (74°C) or until steaming hot.

Hard cheeses (Cheddar, Swiss) and pasteurized-milk options like cottage cheese, cream cheese, & mozzarella.

Homemade versions of your favorite salads (coleslaw, potato, chicken, etc.).

Canned or shelf-stable pâté, meat spreads, and canned fish (like tuna).

Sprouts that have been cooked thoroughly until they are steaming hot.

Cardiovascular Health: Re-evaluating Fats (The 2025 Harvard Study)

For cardiovascular health, the type of fat consumed is paramount. A major 2025 cohort study from researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Mass General Brigham provided powerful new evidence on this topic. The study followed the dietary choices of over 200,000 adults for more than 30 years.

The findings were clear:

Higher intake of butter (rich in saturated fatty acids) was associated with an increased risk of total mortality and cancer mortality.

Higher intake of plant-based oils (rich in unsaturated fatty acids), especially olive, canola, and soybean oils, was associated with a lower risk of premature death from all causes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease.

The most potent and actionable finding from the research centered on a simple substitution. The researchers estimated that replacing just 10 grams per day (less than one tablespoon) of butter with an equivalent amount of plant-based oil was associated with a 17% reduction in premature death and a 17% reduction in cancer mortality.

The Clear and Present Danger: Food Safety for the 65+ Population

A “Senior-Friendly Plate” is not just a nutritious plate; it must also be a safe plate. A critical component of nutritional guidance for older adults, and one that is frequently overlooked, is the significantly elevated risk of foodborne illness.

For this demographic, a foodborne infection is not a mere inconvenience—it is a life-threatening event.

Why Seniors are a High-Risk Group

Adults aged 65 and older are one of the most vulnerable groups for food poisoning. This is not a behavioral risk but a physiological one, driven by the natural changes of aging:

Immunosenescence: The immune system’s response to pathogens grows weaker with age, making it harder to recognize and fight off harmful germs.

Reduced Stomach Acid: The stomach may produce less acid, which normally serves as a first line of defense to kill ingested bacteria.

Slower GI Tract: The gastrointestinal tract may hold food for a longer period, giving bacteria more time to grow and establish an infection.

The pathogen of greatest concern for this group is Listeria monocytogenes. While Listeria infection (listeriosis) is rare, it is exceptionally deadly for seniors.

The CDC reports that more than half of all Listeria infections occur in people 65 and older. The infection almost always requires hospitalization, and the statistic is chilling: 1 in 6 older adults (65+) who get a Listeria infection die.

A Timely Threat: The 2024-2025 Outbreaks

This is not a theoretical danger. A review of recent CDC and FDA investigations reveals a clear and present threat from specific food categories.

July 2024: The CDC and USDA investigated a multistate Listeria outbreak. Epidemiologic and traceback data showed that meats sliced at deli counters, including Boar’s Head brand liverwurst, were contaminated and making people sick.

May 2025: The FDA and CDC investigated a multistate Listeria outbreak (resulting in 10 hospitalizations and 1 death) linked to Ready-to-Eat (RTE) foods, such as sandwiches and snack items, from a single producer.

October 2025: A severe multistate Listeria outbreak was investigated (27 illnesses, 25 hospitalizations, 6 deaths, and one fetal loss) linked to prepared meals containing pasta, such as Chicken Fettuccine Alfredo and Beef Meatball Linguine.

A common thread connects these deadly outbreaks: convenience foods. Seniors, especially those living alone, with mobility challenges, or who are fatigued by cooking, are a primary market for deli meats, pre-packaged sandwiches, and pre-cooked, ready-to-eat meals.

This creates a tragic intersection of risk: the very foods seniors turn to for convenience are the ones that carry the highest risk of a fatal Listeria infection. Listeria is a unique pathogen that can grow even at refrigerator temperatures.

Assembling the Senior-Friendly Plate: A Practical Toolkit

The preceding sections have established the complex physiological, clinical, and safety-related “why” of senior nutrition. This final, extensive section provides the practical “how-to,” translating this body of evidence into actionable strategies, recipes, and resources.

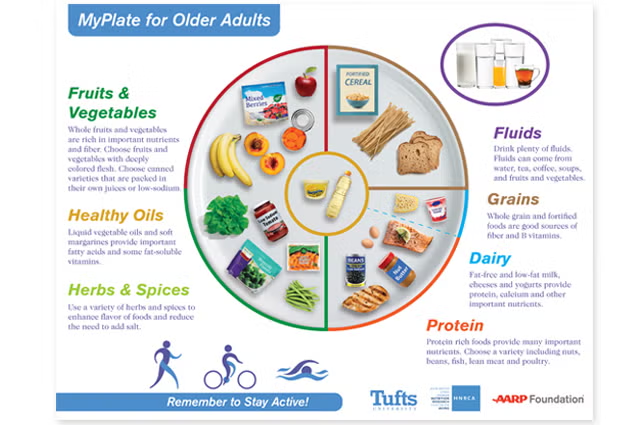

The Blueprint: Why the Tufts “MyPlate for Older Adults” Wins

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) MyPlate is a familiar, evidence-based tool for balanced eating, applicable to all Americans aged 2 and older. While a good starting point, it is a generic guide.

A superior, more specialized tool is the “MyPlate for Older Adults,” developed by nutrition scientists at Tufts University in partnership with the AARP Foundation. This visual guide is specifically tailored to address the unique needs of the 50+ population.

The Tufts plate is more effective because it visually incorporates the specific solutions to the problems outlined in this report:

It Solves for Nutrient Density: Where the USDA plate shows “Vegetables,” the Tufts plate specifies “bright-colored vegetables” (like carrots) and “deep-colored fruit” (like berries). This is a visual cue for the “more-for-less” paradox, emphasizing nutrient-dense choices.

It Solves for Healthy Fats: The Tufts plate explicitly includes an icon for liquid vegetable oils and soft spreads. This directly aligns with the 2025 Harvard study’s findings, encouraging the replacement of saturated animal fats with healthier plant-based oils.

It Solves for Hydration: The Tufts plate adds visual icons for adequate fluids (water, soups, tea). This is a critical addition, as the sense of thirst can diminish with age, making dehydration a common risk.

It Solves for Protein Variety: The plate features icons for beans, nuts, and tofu alongside fish and poultry. This emphasizes diverse, affordable, and often-fortified protein sources necessary to meet higher targets and support B12 intake.

Addressing Practical Barriers: Chewing, Taste, and Convenience

Nutritional plans are useless if they are impractical. A “Senior-Friendly Plate” must account for common physical and logistical challenges.

“Hiding” Vegetables (Low Intake): For seniors who struggle with the taste or texture of vegetables, “hiding” them is a viable strategy.

Smoothies: This is the most effective method. The taste of a large handful of spinach can be completely masked by blending it first with a small amount of liquid (like water or fortified soy milk), then adding frozen fruits like banana, pineapple, or mango, which add sweetness and creaminess.

Eggs and Soups: A large handful of fresh spinach wilts to almost nothing. It can be tossed into scrambling eggs during the last minute of cooking or stirred into a can of (low-sodium) soup just before serving.

Chewing Difficulties (Dental Issues): For seniors with dental problems, dentures, or difficulty swallowing, texture is key. All foods must be soft, but this does not mean they must be bland.

Nutritious Soft-Cooked Options: Mashed potatoes, mashed sweet potatoes, cauliflower cheese, ratatouille (well-stewed vegetables), steamed or boiled carrots (until very soft), pureed vegetable soups (e.g., potato and leek, butternut squash), lentils, flaky baked fish, and applesauce are all excellent, nutrient-dense options.

Batch Cooking for One or Two: Many seniors feel that cooking a full meal is “not worth the trouble” for just one or two people. Batch-cooking is the solution.

Sheet Pan Protein Pancakes: A high-protein pancake batter (using protein powder, Greek yogurt, or cottage cheese) can be poured onto a sheet pan and baked all at once. The resulting “pancakes” can be cut into squares and refrigerated or frozen for an instant, high-protein breakfast.

Cottage Cheese Egg Muffins: Blending eggs with cottage cheese and baking them in a muffin tin creates high-protein, perfectly portioned “egg bites” that can be prepped for the entire week. These two recipes solve both the “30g breakfast” problem and the “cooking for one” problem simultaneously.

Overcoming Barriers: Support Systems and Meal Services

Finally, it is essential to acknowledge the psychosocial and physical barriers to good nutrition. Cooking for one can be a lonely and unmotivating task. Online communities and resources that reframe cooking as an act of self-care and legacy, such as “Home Cooking with Senior Citizen Sue,” can provide social support.

For seniors who are unable to cook due to physical limitations, or who require complex, medically-tailored diets, meal delivery services are a vital tool. This recommendation, however, must be made with the critical food safety issues from Section 4 in mind.

A responsible, evidence-based solution is a vetted meal service that specializes in both safety and clinical nutrition. The AARP, for example, partners with bistroMD to offer members significant discounts.

This service is a direct solution to the problems identified in this report, as it provides “specialty diet meals like heart-healthy, gluten-free, diabetes-friendly, menopause-friendly and more”.

Such services, along with non-profits that deliver medically-tailored meals , solve the complex intersection of challenges facing the senior population.

They provide a safe, convenient alternative to high-risk, store-bought RTE meals while also ensuring adherence to the complex, doctor-recommended diets required to manage hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions

The “Senior-Friendly Plate” is far more than a simple food guide. It is a comprehensive, clinical-practical strategy for empowering older adults to maintain health and resilience. This analysis concludes with five key, actionable principles:

Embrace the “More-for-Less” Paradox: Every meal must be nutrient-dense. This resolves the central challenge of aging: the body’s need for fewer calories but more (or equal) nutrients.

Adopt New Protein Standards: The old RDA of 0.8 g/kg is insufficient. The new, evidence-based targets are 1.0-1.5 g/kg/day. This must be combined with a new timing strategy: aiming for 25-30 grams of protein per meal, especially at breakfast, to overcome anabolic resistance and fight sarcopenia.

Adopt New Protein Standards: The old RDA of 0.8 g/kg is insufficient. The new, evidence-based targets are $1.0-1.5 g/kg/day. This must be combined with a new timing strategy: aiming for 25-30 grams of protein per meal, especially at breakfast, to overcome anabolic resistance and fight sarcopenia.

Use “Smart Swaps” for Disease Management: Simple, one-for-one substitutions are powerful tools. Swapping butter for olive oil (17% reduced mortality risk), reading the “Added Sugars” label (aim for <5% DV), and—with physician approval—using a salt substitute (40% reduced hypertension risk) are all evidence-based interventions.

Use the Right Tools: The Tufts University “MyPlate for Older Adults” is the superior visual guide, as it accounts for nutrient density, healthy fats, and hydration. For those who cannot cook, vetted, medically-tailored meal services are a safe and effective solution to manage chronic disease.