Tasty and Simple Plant-Based Recipes for Seniors: Nutrition That Tastes (and Feels) Amazing

If you feel your energy fading despite eating “sensibly,” your morning routine might be silently accelerating muscle loss. New 2025 research exposes how traditional senior meals often fail to combat sarcopenia, the age-related decline that steals independence.

The good news is that you don’t need complex diets to fight back. This guide reveals the specific “lean and simple” ingredient swaps—from the “4-hour thyroid rule” for protein to the “massaged” superfood technique—that can instantly boost your vitality.

Discover how to trick your body into building muscle again with meals that taste indulgent but work like medicine to keep you strong, sharp, and incredibly active.

🍽️ The “Sarcopenia Shield” Protein Guide

1. The 2026 Geriatric Nutritional Landscape: A Paradigm Shift from Lifespan to Health span

The demographic reality of 2026 presents a complex physiological and psychosocial challenge: a rapidly aging population that is living longer but often with comprised functional independence.

The prevailing nutritional guidance for older adults has fundamentally shifted from a generalized focus on “longevity”—simply keeping patients alive—to a targeted, interventionist approach centered on “healthspan,” or the quality of life and functional capability during the later years.

This transition is driven by the recognition that the biological machinery of the aging body operates under different rules than that of the younger adult, necessitating a nutritional strategy that is not merely a scaled-down version of a standard diet, but a specifically engineered protocol to combat senescence.

In this contemporary landscape, the concept of “lean and simple” meal planning for seniors is no longer just about caloric restriction or culinary convenience; it has become a clinical necessity to address the “Processing Paradox.”

This paradox, a defining trend of 2026, highlights the tension between the senior consumer’s need for accessible, easy-to-prepare foods and the biological imperative for nutrient-dense, whole-food nutrition that avoids the inflammatory pitfalls of ultra-processed alternatives.

As global life expectancy rises, the focus has narrowed on specific physiological targets: muscle health to prevent frailty, joint health to maintain mobility, and cognitive preservation.

The Intersection of Policy, Economics, and Nutrition

Significant shifts in public health policy and economic realities shape the broader context of senior nutrition in 2026.

There is an increasing awareness of health equity, driving a rise in culturally responsive menus and the expanded use of “medically tailored meals” as a standard intervention for chronic disease management.

This suggests that meal planning must be adaptable to diverse cultural palates while maintaining rigorous nutritional standards. Furthermore, the economic uncertainty regarding government funding for senior nutrition programs places a premium on cost-effective, nutrient-dense ingredients.

The “lean” in “lean and simple” thus refers not only to the lipid profile of the food but also to the economic efficiency of the grocery list, maximizing the nutritional return on investment for every dollar spent by the senior or their caregiver.

Simultaneously, the threat landscape has evolved to include emergency preparedness as a core component of nutritional planning.

Seniors are increasingly advised to maintain non-perishable, nutrient-dense stockpiles—such as canned legumes, shelf-stable proteins, and fortified beverages—to ensure continuity of nutrition during climate events or supply chain disruptions.

This “resilience nutrition” perspective requires that simple meal ideas be translatable to pantry-staple cooking, ensuring that a senior can maintain muscle mass even when fresh food access is temporarily compromised.

Psychosocial and Behavioral Determinants

Nutritional uptake in the elderly is heavily influenced by behavioral and sensory changes. A critical barrier to adequate protein consumption is the alteration of taste perception (dysgeusia) and a general decline in appetite (anorexia of aging), often exacerbated by polypharmacy.

Once palatable food may taste bland or metallic to the 2026 senior, leading to a reduction in intake. Consequently, “simple” meals cannot be flavorless; they must utilize herbs, spices, and texture contrasts to stimulate the flagging appetite.

Social isolation remains a potent co-morbidity. The trends for 2026 emphasize the vital role of staying socially connected, as communal dining improves caloric intake and mental health. However, for the senior cooking alone, the motivation to prepare elaborate meals diminishes.

The data indicate that snacking behaviors are shifting, with 47% of seniors consuming fruit daily as a snack, while 35% consume nuts and seeds weekly.

This snacking behavior is a leverage point: meal ideas must be modular and snack-able, blurring the lines between a “meal” and a “nutrient event” to accommodate smaller, more frequent feeding windows.

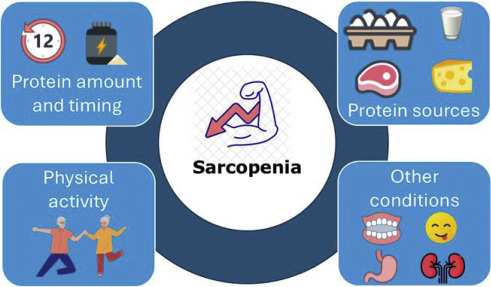

2. Physiological Imperatives: Sarcopenia and the Protein Threshold

The central biological antagonist in senior health is sarcopenia—the age-related, involuntary loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength. This condition is not merely a side effect of aging; it is a primary driver of frailty, disability, loss of independence, and mortality.

The 2025 nutritional guidelines have crystallized around the understanding that the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 0.8 g/kg/day, which suffices for younger adults, is grossly inadequate for the elderly population due to the phenomenon of anabolic resistance.

The New Protein Mathematics of 2026

Anabolic resistance refers to the blunted response of older muscle tissue to amino acids. To achieve the same level of Muscle Protein Synthesis (MPS) as a younger individual, a senior requires a significantly higher dose of protein.

Recent authoritative research and commissioned studies have recalibrated the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) for older adults with sarcopenia to 1.21 g/kg/day, with a Recommended Nutrient Intake (RNI) reaching up to 1.54 g/kg/day.

For a senior weighing 150 pounds (approx. 68 kg), the outdated guidance would suggest a mere 54 grams of protein daily. The 2025 evidence-based guidelines, however, mandate a minimum of roughly 82 to 105 grams daily to maintain muscle mass.

A simplified heuristic for seniors in 2025 is to divide their body weight in pounds by two, and then multiply by 1.2 to determine their daily minimum target. This mathematical reality necessitates that protein can no longer be an afterthought or a side dish; it must be the central anchor of every dietary event.

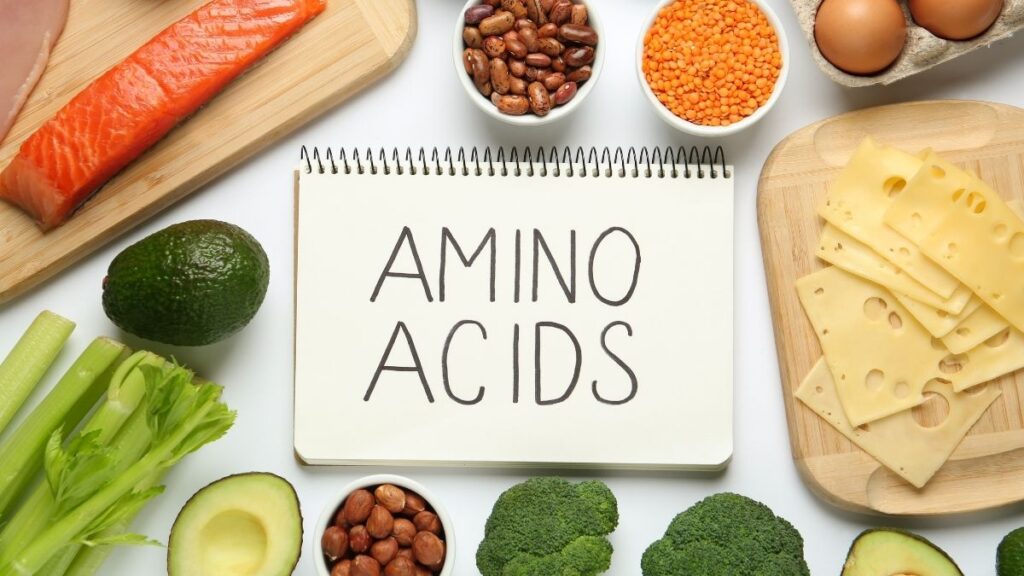

Amino Acid Profiling and the Leucine Trigger

The quality of protein is as critical as the quantity. The primary trigger for MPS is the essential amino acid L-Leucine.

Comparative studies analyzing the amino acid profiles of reference proteins against standard dietary intakes show that seniors often fall short in consuming adequate essential amino acids, particularly Methionine, Lysine, and Leucine, when relying on lower-quality protein sources.

Research indicates that even when total protein intake is increased to 1.8 g/kg, the bioavailability and amino acid composition vary significantly between sources. Lean meats, poultry, eggs, and seafood remain the most efficient delivery mechanisms for these amino acids.

For instance, a single chicken breast can provide approximately 40 grams of high-leucine protein, immediately surpassing the 30-gram anabolic threshold required per meal.

However, as dietary patterns shift toward sustainability, the reliance on plant-based proteins requires careful navigation to ensure this leucine threshold is met without consuming excessive calories.

The “Lean” Constraint: Caloric Efficiency vs. Protein Density

A significant challenge in senior nutrition is the decrease in Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR). As activity levels and muscle mass decline, the total caloric requirement drops, yet the protein requirement rises.

This creates a narrow nutritional corridor: seniors must consume more nutrients in fewer calories. This is the definition of “nutrient density.”

High-fat protein sources, while palatable, often carry a caloric penalty that can lead to unwanted fat mass accretion, which is detrimental to metabolic health.

Therefore, “lean” protein sources—skinless poultry, white fish (cod, haddock), egg whites, and low-fat dairy (cottage cheese, Greek yogurt)—are paramount. These foods offer a high protein-to-calorie ratio, allowing the senior to hit the 1.2 g/kg target without exceeding their daily energy expenditure.

Conversely, while plant-based diets are strongly advocated for longevity, relying solely on lower-density plant proteins (like standard beans) can make hitting the protein target volumetrically difficult for seniors with early satiety.

3. Functional Ingredient Analysis: The Plant-Based Shift and Superfoods

The 2026 nutritional zeitgeist heavily favors plant-based eating patterns for their association with reduced all-cause mortality and improved cardiovascular outcomes.

Studies from Vanderbilt University Medical Center and global longevity research confirm that diets rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes significantly lower the risk of premature death.

However, for the senior population, the selection of these plant foods must be strategic, balancing the benefits of phytochemicals with the risks of anti-nutrients and medication interactions.

The Soy Spectrum: Tofu, Tempeh, and Thyroid Considerations

Soy foods are a cornerstone of plant-based senior nutrition due to their complete amino acid profile and cardiovascular benefits, including LDL cholesterol reduction. However, the choice between tofu and tempeh represents a significant functional distinction.

Tofu: As a coagulated soy curd, tofu is nutritionally valuable for its high calcium content (essential for osteopenia prevention) and its soft texture, which accommodates dental dysphagia.

It is lower in calories than tempeh, making it suitable for weight management, but it lacks the prebiotic fiber found in whole beans.

Tempeh: This fermented soybean cake is increasingly recognized as superior for seniors concerned with gut health. The fermentation process not only improves digestibility by breaking down oligosaccharides but also generates probiotics and prebiotics that support the gut microbiome.

Crucially, recent studies have shown that tempeh consumption, when combined with resistance exercise, creates a stronger immune response (measured by secretory IgA levels) compared to tofu. With 18g of protein per 3-ounce serving compared to tofu’s lower density, tempeh is the more “anabolic” choice.

The Thyroid Interaction Protocol: Despite these benefits, a critical medical contraindication exists. Hypothyroidism is prevalent in the elderly population, commonly treated with Levothyroxine.

Soy isoflavones can physically interfere with the absorption of this medication in the gastrointestinal tract. The 2026 guidelines dictate a strict temporal separation: seniors must wait at least four hours after taking thyroid medication before consuming soy products to ensure efficacy.

Failure to observe this window can lead to fluctuating TSH levels and symptom re-emergence.

The Fava Bean Renaissance: Neuro-Nutrition and Hematological Risk

Fava beans (broad beans) have re-emerged in 2026 as a high-protein, sustainable crop, frequently utilized in “soy-free” tofu alternatives that boast impressive protein-to-calorie ratios. Beyond their macronutrients, fava beans are a rich natural source of Levodopa (L-dopa), the precursor to dopamine.

Neuro-Nutritional Benefits: For seniors with Parkinson’s Disease (PD), fava beans can act as a functional food adjunct to therapy. Consumption has been shown to significantly increase plasma L-dopa levels, potentially improving motor performance.

Some patients report a smoother, more prolonged effect compared to synthetic medications alone.

The Risk Profile (Favism and CVD): However, fava beans present a severe risk for individuals with Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, a genetic condition that affects a significant portion of the population.

In these individuals, the compounds vicine and convicine found in fava beans can trigger acute hemolytic anemia (favism), leading to jaundice, renal failure, and potential fatality.

While often diagnosed in childhood, cases of favism in the elderly are documented, sometimes presenting as acute renal failure in seniors who had previously consumed the beans without incident.

The “Massaged Kale” Mechanism: Enhancing Digestibility

Dark leafy greens like kale are non-negotiable for their Vitamin K (bone density) and magnesium (blood pressure/muscle function) content. Yet, the fibrous nature of raw kale makes it difficult for seniors with reduced masticatory force or lowered gastric acid to digest, leading to avoidance.

The “massaged kale” technique addresses this by using mechanical action and lipids (olive oil) or acids (lemon juice) to break down the cellulose cell walls prior to consumption.

This process softens the leaves, reduces bitterness (making it more palatable to altered taste buds), and increases the bioavailability of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) without the nutrient loss associated with boiling or steaming. This transforms a “difficult” superfood into a manageable staple.

Glycemic Control: The Banana vs. Date Paradigm

For the millions of seniors managing pre-diabetes or Type 2 Diabetes, fruit selection is critical.

Bananas: While popular for their texture and potassium, their glycemic index (GI) is highly variable. A ripe (yellow/brown) banana has a high GI, causing rapid blood sugar spikes. A green banana contains resistant starch, which blunts the glucose response and feeds gut bacteria, but is less palatable.

Dates: Despite their high sugar density, dates exhibit a lower glycemic index than expected due to their fiber matrix and fructose content. Studies indicate that moderate date consumption does not significantly spike postprandial blood glucose in diabetic patients.

Strategic Choice: For sweetening oatmeal or smoothies, dates offer a safer glycemic profile and higher fiber content than ripe bananas, making them the superior choice for metabolic stability.

🥗 The 2025 Senior Superfood Upgrade

Gut Health & Protein

Tofu vs. Tempeh

Tofu: Great for calcium, soft texture.

Tempeh: The “Probiotic Powerhouse” with 18g protein per serving + gut-friendly fermentation.

Glycemic Stability

Ripe Banana vs. Dates

Ripe Banana: High Glycemic Index (can spike blood sugar).

Dates: Offer sweetness with a lower glycemic impact and higher fiber for steady energy.

Digestibility

Raw Kale Salad vs. “Massaged” Kale

Raw Kale: Stiff, pokey leaves are tough on digestion.

“Massaged” Kale: Massaging with olive oil/lemon breaks down cellulose, making it softer and easier to digest without cooking away vitamins.

4. Ergonomics of Nutrition: Addressing Physical Barriers to Intake

A meal is only nutritious if it can be prepared and consumed. In 2026, the definition of “simple” meal planning must extend to the biomechanics of the kitchen.

Arthritis, reduced grip strength (dynapenia), and neuropathy act as physical gatekeepers to healthy eating, often forcing seniors toward pre-packaged, high-sodium convenience foods.

Adaptive Culinary Tools

The “Ergonomic Kitchen” is a therapeutic intervention. The inability to open a jar or chop a vegetable is a primary failure point in senior nutrition.

Jar and Can Access: Vacuum-sealed jars are notoriously difficult. Adaptive aids like silicone grippers, under-cabinet openers, or automatic button-press vacuum release tools are essential to grant access to high-quality staples like nutrient-dense sauces or pickled vegetables.

Cutting and Chopping: The traditional knife grip requires significant wrist stability and grip force. “Rocker knives” (which use downward pressure and a rocking motion) or “L-handled” knives allow the wrist to remain neutral, reducing pain and leveraging arm strength rather than hand strength.

Alternatively, the use of food processors or purchasing pre-chopped frozen vegetables removes this barrier entirely.

Safety Surfaces: Non-slip cutting boards with spikes to hold food in place allow for one-handed preparation, vital for stroke survivors or those with hemiparesis.

Food Safety and Immunosenescence

The aging immune system (immunosenescence) makes seniors significantly more susceptible to foodborne pathogens like Listeria and Salmonella. A “simple” meal must also be a safe one.

The physiological decline in stomach acid production reduces the body’s natural barrier to bacteria. Therefore, strict adherence to the “Clean, Separate, Cook, Chill” protocol is mandatory.

Practical Implication: While pre-bagged salads are convenient, they carry Listeria risks. Cooking greens (or blanching them) is safer than raw consumption for the immunocompromised.

Frozen vegetables, which are flash-cooked before freezing, offer a safety advantage over raw produce that requires meticulous washing.

Digital Accessibility of Nutritional Information

In 2026, seniors are increasingly accessing recipes and nutritional advice via mobile devices and tablets. However, visual impairments (presbyopia, cataracts) and motor tremors make standard web interfaces challenging. Nutritional content must adhere to WCAG 2.2 standards.

Typography and Contrast: Text must be scalable without breaking layout (reflow), utilizing sans-serif fonts (Arial, Verdana) for legibility. High contrast ratios (black text on white, or yellow on black) are essential for low-vision users.

Interface Design: Interactive elements (like “jump to recipe” buttons) must have large touch targets to accommodate reduced dexterity and tremors.

Cognitive Load: Instructions should be step-by-step and error-tolerant, avoiding complex, timed multi-tasking which can overwhelm cognitive processing speeds.

5. Synergistic Interventions: The Role of Exercise and Lifestyle

Nutritional interventions for sarcopenia are largely ineffective in isolation. The “anabolic resistance” of aging muscle can be partially overcome by protein, but it requires the mechanical signal of resistance exercise to be fully reversed.

Fast-Twitch Muscle Preservation

Aging results in the preferential atrophy of Type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibers—the fibers responsible for power, speed, and catching oneself during a trip. Type I (slow-twitch) fibers are generally better preserved.

The Exercise Requirement: Walking (an endurance activity) does not stimulate Type II fibers. To preserve these, seniors must engage in resistance training or “power” training—moving a weight (or body weight) with intent and speed.

Flywheel exercises and plyometrics (modified for safety) have shown promise in recruiting these fibers in older populations.

Movement Snacking: The concept of “exercise snacking”—short bouts of activity throughout the day—aligns with the “protein pacing” strategy. Performing a set of sit-to-stands rapidly before a high-protein meal sensitizes the muscle tissue to the incoming amino acids, optimizing the anabolic response.

Hydration and Renal Health

With the recommendation for higher protein intake comes the necessity for increased hydration. Protein metabolism produces nitrogenous waste (urea), which increases the renal solute load. Since seniors often experience a diminished thirst sensation, they are at risk for chronic sub-clinical dehydration.

Strategy: “Wet” meals are preferable. Soups, stews, and smoothies provide simultaneous hydration and nutrition. Herbal teas and infused water should be encouraged to replace sugary beverages, supporting both kidney function and glycemic control.

6. Practical Application: The “Lean & Simple” Framework for 2025

Synthesizing the physiological data, the medical constraints, and the ergonomic realities, we can construct a “Lean and Simple” meal framework that is scientifically robust.

Breakfast: The Anabolic Primer

The traditional senior breakfast of toast and coffee is a nutritional failure in the context of sarcopenia. The overnight fast induces catabolism; breakfast must arrest this.

The Concept: “Power Oats.”

Mechanism: Steel-cut oats (fiber) cooked with dates (safe sweetener) and fortified with egg whites or whey protein isolate stirred in at the end.

Nutritional Target: >30g protein.

Why: This combines the fiber needed for gut health with the high-leucine protein needed to trigger morning muscle synthesis, all with a soft texture and low glycemic impact.

Lunch: The No-Cook Nutrient Density

Lunch is often the time of highest energy but lowest cooking motivation.

The Concept: “The Omega Bowl.”

Ingredients: Canned wild salmon (using an ergonomic opener), mixed with pre-massaged kale (prepared in bulk weekly) and white beans.

Mechanism: Salmon provides Omega-3s for joint health and cognitive protection , while the bones in canned salmon provide calcium. The kale offers Vitamin K.

Ergonomics: Zero chopping required if using canned beans/fish and bagged kale.

Dinner: The Gut-Restorative Stew

Dinner should focus on digestibility and repair.

The Concept: “Tempeh Turmeric Stew.”

Ingredients: Tempeh cubes simmered in bone broth with frozen root vegetables.

Mechanism: The fermentation of tempeh aids digestion before sleep. The broth provides collagen precursors.

Medical Note: This meal is soy-heavy. If the senior takes thyroid medication in the morning, this evening meal is safely outside the 4-hour interaction window.

The Snack Strategy: Protein Pacing

Given the trend toward snacking , the “snack” should be viewed as a “Fourth Meal” for protein distribution.

Options: Greek yogurt with chia seeds; a handful of almonds (approx. 6g protein) ; or a fava-bean based dip (assuming no G6PD deficiency).

Goal: To keep the amino acid pool topped up between main meals, preventing the body from scavenging muscle tissue for energy.

7. Market Insights and Search Behavior: What Seniors Are Seeking

Understanding the “user intent” of the senior demographic in 2026 clarifies their anxieties and needs. SEO analysis reveals high search volumes for “diet plan for weight loss” (135k volume) and “banana nutrition” (90.5k volume).

This indicates a conflict: seniors are concerned about excess weight (likely visceral fat) but are searching for simple, familiar foods like bananas.

The Content Gap: There is a massive opportunity to educate this demographic that “weight loss” in their age bracket must be “fat loss,” not “muscle loss.” The search for “low-calorie meals” needs to be redirected toward “high protein, calorie-efficient meals.”

Emerging Keywords: Terms like “protein powder for weight gain” and “diabetic diet” suggest a split demographic: the frail seeking bulk, and the metabolic syndrome patient seeking control. The “Lean and Simple” framework addresses both by focusing on muscle-centric nutrition that regulates blood sugar.

Conclusion

The “Lean and Simple” meal for the senior of 2026 is a sophisticated intersection of geriatric physiology, food chemistry, and ergonomic design. It rejects the notion that senior nutrition is merely about “soft food” or “low salt.”

Instead, it embraces a proactive, high-protein strategy to combat sarcopenia, utilizing functional ingredients like tempeh and fava beans to target specific biological pathways—from the gut microbiome to dopaminergic signaling.

By integrating the mechanical “massaging” of greens, the careful timing of soy consumption, and the use of adaptive kitchen tools, this approach removes the physical and biological barriers to healthy eating.

It acknowledges that the battle for independence is fought in the kitchen, and that every 30-gram serving of protein is a direct investment in the ability to stand, walk, and live freely.

The synthesis of exercise and nutrition—”power snacking” and “protein pacing”—offers the most robust defense against the decline of aging, transforming the later years from a period of management to a period of vitality.