The Meat vs. Vegetarian Health Debate: Uncovering the Real Key to a Healthy Diet (Who’s Actually Healthier)

For decades, a fierce debate has raged across dinner tables, social media feeds, and scientific journals: meat eaters versus vegetarians. The battle lines seem clearly drawn, with each side armed with studies and passionate arguments for their dietary supremacy.

Yet, after years of research, a clear verdict has emerged, and it is not the one either side expected. The conflict has been waged on the wrong battlefield.

The real story of human health is not about choosing a side in a binary war between carnivores and vegans; it is about understanding a fundamental principle that both camps often ignore.

Much of the confusion has been fueled by a persistent flaw in early research: comparing the health of a “health-conscious vegetarian” to that of an “average meat-eater” who often consumes a Standard American Diet (SAD) laden with processed foods.

Case Title Placeholder

Summary placeholder.

Key Findings:

The Case for Plants – Unpacking the Health Halo

The foundation of any healthy diet is built upon plants. The evidence supporting a plant-centric eating pattern is robust, demonstrating clear and measurable benefits for reducing the risk of chronic disease and fostering a healthy internal ecosystem. These advantages are not magical but are rooted in the specific biological mechanisms driven by the nutrients and compounds found in whole plant foods.

A Shield Against Chronic Disease

A well-planned vegetarian or vegan diet has been consistently linked to a reduced risk of many of the most prevalent chronic diseases of the modern world.

Large-scale studies show that individuals following these dietary patterns have lower rates of obesity, coronary heart disease, hypertension (high blood pressure), type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer. One analysis even quantified the cancer risk reduction for vegetarians at 14%.

The Microbiome Miracle – Your Inner Garden

The trillions of microorganisms residing in the human gut, collectively known as the gut microbiome, are now recognized as a cornerstone of overall health. Diet is the single most powerful factor shaping this internal ecosystem, and here, plant-based diets show a profound advantage.

Plant fibers, which are non-digestible carbohydrates found exclusively in plants, act as prebiotics—food for beneficial gut bacteria.

These fibers promote the growth of species like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which are associated with anti-inflammatory effects, cardiovascular protection, and a robust immune system.

A plant-rich diet fosters a more diverse and stable microbial system, which is a hallmark of good health.

The Nutrient Question – Planning for Completeness

To maintain credibility, it is essential to acknowledge that while plant-based diets can be exceptionally healthy, they require conscious planning to ensure nutritional adequacy. Eliminating entire food groups without careful replacement can lead to deficiencies in several key nutrients.

Vitamin B12: This vitamin is crucial for nerve function and is not naturally present in plant foods.

Iron: Plants contain non-heme iron, which is less readily absorbed by the body than the heme iron found in meat.

Calcium and Bone Health: Some studies indicate that vegans may have lower calcium intake, which can lead to higher rates of bone turnover and a slightly increased risk of fractures compared to meat-eaters.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids: The most potent anti-inflammatory omega-3s, EPA and DHA, are found almost exclusively in fatty fish.

Choline: This essential nutrient, vital for brain and liver health, is found predominantly in animal foods like eggs and liver.

These challenges are not insurmountable but highlight the need for a well-planned diet. The following table provides a practical guide for meeting these nutrient needs.

The Case for Meat – More Than Just a Villain?

While the benefits of a plant-rich diet are clear, a nuanced discussion requires an honest assessment of animal foods.

The narrative that universally condemns meat as unhealthy is an oversimplification that ignores nutrient density and, most importantly, fails to distinguish between different types of meat products.

The Unmatched Nutrient Density of Animal Foods

Animal foods are exceptionally nutrient-dense. They provide a complete source of high-quality protein, containing all nine essential amino acids in proportions ideal for human needs.

Furthermore, they are the most reliable and bioavailable sources of certain critical nutrients, including heme iron and vitamin B12, which are either less absorbable or entirely absent from plant foods.

For certain individuals or populations, meeting requirements for these nutrients without animal products can be a significant challenge, requiring diligent planning and supplementation.

The Real Culprit – Separating the Steak from the Sausage

The most significant breakthrough in understanding the health risks associated with meat comes from distinguishing between unprocessed and processed forms.

The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has provided clear classifications that should guide public health messaging.

Processed meat—defined as meat that has been transformed through salting, curing, fermentation, smoking, or other processes to enhance flavor or improve preservation (e.g., hot dogs, bacon, sausage)—is classified as a Group 1 carcinogen, meaning there is sufficient evidence that it causes cancer in humans.

The data is strikingly specific: every 50-gram portion of processed meat consumed daily increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18%.11

Hormones & Mental Health – A Sober Look at Murky Waters

The debate over diet is often clouded by sensational claims regarding mental and hormonal health. A sober look at the scientific literature reveals these waters to be murky and inconclusive.

On the topic of mental health, the evidence is deeply conflicted. Some systematic reviews suggest that individuals who abstain from meat have higher rates of depression or anxiety, while other studies show the opposite or no association at all.

Critically, the authors of these reviews consistently highlight significant methodological flaws, including a high risk of bias and the inability to establish a causal relationship.

It is impossible to determine whether a dietary choice leads to a mood disorder or if individuals with certain psychological predispositions are more likely to adopt a specific diet. Given the poor quality of the evidence, making strong claims about diet and mental health is not scientifically supported.

Part III: The “Shocking Secret” Revealed – It’s Not the Cow, It’s the How

The climax of this dietary investigation arrives with the revelation that the lines have been drawn in the wrong place. The true determinant of health is not the ideological camp one belongs to, but the quality of the food one consumes.

This is most evident in the rise of ultra-processed foods that wear a “plant-based” halo and in the dietary patterns of the world’s longest-lived populations.

The Ultra-Processed Problem – When “Plant-Based” Becomes Junk Food

Compare Diet Patterns

Lowers CVD & Diabetes Risk

Longevity & Low Chronic Disease

Low Chronic Disease Risk

The Whole-Food Omnivore – Lessons from the World’s Longest-Lived People

The most compelling evidence for an optimal human diet comes not from a short-term clinical trial but from real-world populations who have achieved extraordinary longevity.

The “Blue Zones” are five regions around the world—Okinawa, Japan; Sardinia, Italy; Nicoya, Costa Rica; Ikaria, Greece; and Loma Linda, California—with the highest concentrations of centenarians.

While their specific foods vary, their core dietary principles are remarkably consistent. Their diets are overwhelmingly plant-based, with an estimated 95% of their food intake coming from vegetables, fruits, grains, and legumes.

However, with the notable exception of the Seventh-day Adventists in Loma Linda, they are not strictly vegetarian.

Meat is consumed, but sparingly—typically in small, two-ounce portions about five times per month, often as a celebratory food or a condiment to flavor plant dishes.

The Flexitarian Advantage – Finding the Sweet Spot

The dietary pattern embodied by the Blue Zone populations now has a modern name: flexitarianism. This approach, defined by a primarily plant-based diet with the occasional inclusion of high-quality animal products, is gaining significant support from clinical research.

A landmark 2024 study published in BMC Nutrition compared the cardiovascular risk factors of long-term flexitarians, vegans, and omnivores. The results were illuminating.

Both flexitarians and vegans showed more beneficial levels of insulin, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol compared to the omnivore group.

However, the study revealed a fascinating nuance: flexitarians exhibited more favorable results for metabolic syndrome and had better measures of arterial stiffness than both the vegans and the omnivores.

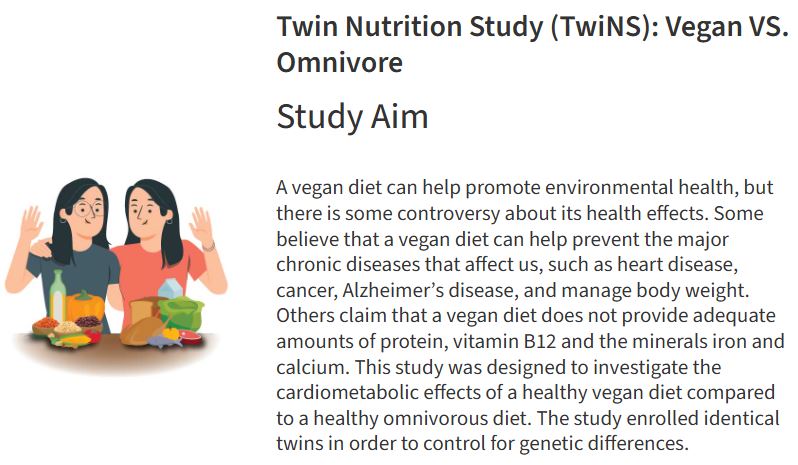

The Definitive Experiment? The Stanford Twin Study

To isolate the effects of diet from the powerful influence of genetics, a 2023 Stanford University study conducted a randomized clinical trial on 22 pairs of identical twins.

For eight weeks, one twin in each pair was assigned a healthy, whole-food vegan diet, while the other was assigned a healthy, whole-food omnivorous diet. Both diets emphasized vegetables, legumes, fruits, and whole grains and minimized refined sugars and starches.

A study on twins revealed that those following a vegan diet showed more significant improvements in heart health markers compared to their omnivorous siblings. The vegan twins had notable reductions in “bad” LDL cholesterol, lower fasting insulin, and greater weight loss.

Although the study was short-term and weight loss was linked to lower calorie consumption, its design strongly suggests that a plant-exclusive diet provides additional protective benefits. This reinforces the idea that maximizing whole plant foods is a powerful strategy for better health.

To visualize how these different dietary patterns relate to health outcomes, the following table organizes them not by their label, but by their quality.

Your Actionable Guide for a Healthier 2025

Translating this wealth of scientific evidence into daily practice does not require a radical or dogmatic overhaul. Instead, it involves adopting a set of simple, universal principles that can guide food choices for anyone, regardless of their dietary label.

The Four Universal Principles of Healthy Eating

Prioritize Whole Foods: The cornerstone of a healthy diet is to consume foods in a form as close to their natural state as possible. This means building meals around vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds.

Maximize Plant Diversity: Aim to “eat the rainbow.” A wider variety of plant foods provides a broader spectrum of vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients, and fosters a more diverse and resilient gut microbiome.

Minimize Ultra-Processed Products: Be a skeptical consumer. If a food product comes in a package with a long list of unfamiliar ingredients, it is likely ultra-processed and should be consumed sparingly. This rule applies equally to a vegan sausage and a conventional candy bar.

Plan for Nutrient Gaps: Understand the potential nutritional shortfalls of any chosen dietary pattern. For vegans, this means ensuring a reliable source of vitamin B12. For all eaters, it means ensuring adequate intake of nutrients like omega-3s and vitamin D, through food or targeted supplementation.

Building Your Resilient Plate – A Visual Guide

A simple heuristic can make healthy eating intuitive. Visualize a plate and apply the 75/25 principle:

Aim for at least 75% of the plate to be filled with plants: This includes a large portion of non-starchy vegetables (like leafy greens, broccoli, bell peppers), a serving of fiber-rich carbohydrates (like quinoa, sweet potato, or beans), and healthy fats (like avocado or olive oil).

The remaining 25% is for a high-quality protein source: This can be more plants (such as lentils, tofu, or edamame) or a small, palm-sized portion of unprocessed animal food (such as grilled fish, eggs, or free-range chicken).

This model provides a practical, flexible framework that automatically aligns a diet with the principles observed in the world’s healthiest populations.

Beyond Health – A Note on the Environment

The environmental impact of food choices is a complex and important consideration. Industrial animal agriculture is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and water use.

However, the narrative is not one-sided. Industrial plant agriculture, particularly the practice of monocropping (growing a single crop over vast areas), also has significant environmental downsides, including biodiversity loss, soil degradation, and heavy reliance on chemical pesticides and fertilizers.

An emerging “third way” is regenerative agriculture, a system of farming that often integrates livestock in a way that mimics natural ecosystems.

Practices like rotational grazing can improve soil health, enhance water retention, increase biodiversity, and even sequester carbon from the atmosphere, challenging the notion that all animal farming is inherently destructive.

The most sustainable dietary choice, therefore, involves reducing the consumption of all industrially produced foods—both plant and animal—and, where possible, supporting farming systems that regenerate rather than deplete the environment.

Conclusion: A New Verdict for the 21st Century

The long-standing war between meat eaters and vegetarians has been fought on false pretenses. The winner is neither.

The true victor is the individual who transcends dietary dogma and embraces a unifying principle: a diet centered on whole, minimally processed, and diverse plant foods is the foundation for a long and healthy life.

The evidence is clear that this foundation can be built with or without the inclusion of small amounts of high-quality animal products.

The real threat to our collective health is not the steak or the tofu, but the factory-formulated, ultra-processed products that have come to dominate the modern food supply, often disguised with misleading health claims.

The power to transform one’s health does not lie in joining a dietary tribe or adhering to a rigid set of rules. It lies in the daily, conscious choices made in the grocery aisle and the kitchen.

Forget the labels. Focus on the food. That is the real secret to health and longevity in 2025 and beyond.